Scientists are looking for effective ways to preserve the region's rich resources. Hou Liqiang and Li Yingqing report from Xishuangbanna, Yunnan.

Southeast Asia is renowned as one of the regions with the richest biodiversity resources in the world. However, this valuable asset is being increasingly endangered by climate change and deforestation undertaken for economic development.

As the clock for action ticks ever faster, Chinese scientists have been ratcheting up efforts to promote biodiversity conservation in countries in the region that have inadequate protection capabilities.

While immersing themselves in sweltering jungles during field expeditions, they have also upped the ante in terms of building capacity, hoping to help the affected nations build their own research teams for protection work.

In May, the scientists and counterparts from Myanmar entered jungles in North Myanmar for the eighth joint China-Myanmar expedition, which lasted more than 30 days.

They were welcomed by a heat wave, with temperatures rising higher than 40 C, leaving some of the 40-strong team with sunstroke not long after the expedition started.

For three consecutive days after the launch "heat wave" was a key term in the diary of Quan Ruichang, executive deputy director of the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In each of his diary entries, Quan repeated the Chinese character re ("hot") three times to underline the extreme temperatures.

"Previously, we had never worked amid a heat wave of more than 40 C all day long," Quan said.

A 10-second video clip provided by the institute provides an impressive example. The moment a scientist, arms beaded with sweat, set his right hand on a long bench, the part of the bench he had touched was left dripping wet, as if a small cup of water had been poured over it.

Chinese researcher Qin Tao sorts fish specimens. [Photo/Xinhua]

Challenges

The difficulties the researchers encountered went even further. Though it was the eighth expedition the institute had conducted with Myanmar's Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Quan said it threw the team into a completely new and strange environment that posed a range of challenges.

Instead of trekking across mountains as previous expeditions had done, the scientists were able to proceed in small boats, thanks to the interconnected waterways in the low-altitude region.

However, they faced safety threats because of the great number of large animals in the area, including elephants and tigers. Elephants cause many casualties every year, but the team frequently had to work near the largest land animals, he said.

Communication with the outside world can be hard in the depopulated zone, so contact with families was a luxury that could only be enjoyed once every 10 days, he added.

Though the difficulties went far beyond what he could describe, Quan stressed that field expeditions play a significant role in the protection of biodiversity.

"It's very important to learn about the environment (for flora and fauna), which is key for their protection. Without adequate understanding of these key factors, it can be hard to 'shoot the arrow at the target' when drafting protective measures," he said.

Song Liang, an associate researcher at the CAS Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden who has participated in joint field expeditions in Myanmar and Laos, said the limited road access and a lack of food in the areas they visited meant the researchers not only had to carry their own equipment, but also all the food they would need.

In addition to establishing a center in Myanmar's capital Naypyidaw in 2016, the biodiversity institute established an office in Laos last year. So far, three China-Laos joint expeditions have been carried out in Laos. Song's botanical garden is now in charge of the institute's operations.

"Every scientist needed the support of four or even five workers to help carry equipment and daily necessities," he said.

The consumption of food didn't mean the weight on their backs gradually reduced, because the scientists had to carry a growing number of specimens as they proceeded.

Song said it was common for his colleagues to enter pathless jungles to collect specimens, which needed to be dried the day they were collected. However, with no power available on many occasions, the work can be extremely difficult in the rainy season, so his colleagues often worked until midnight.

The scientists' efforts have paid off, though, Quan said. Although Western experts had previously undertaken field expeditions on biodiversity to northern Myanmar, papers published by Chinese scientists in the past three years have outnumbered those published by their Western counterparts.

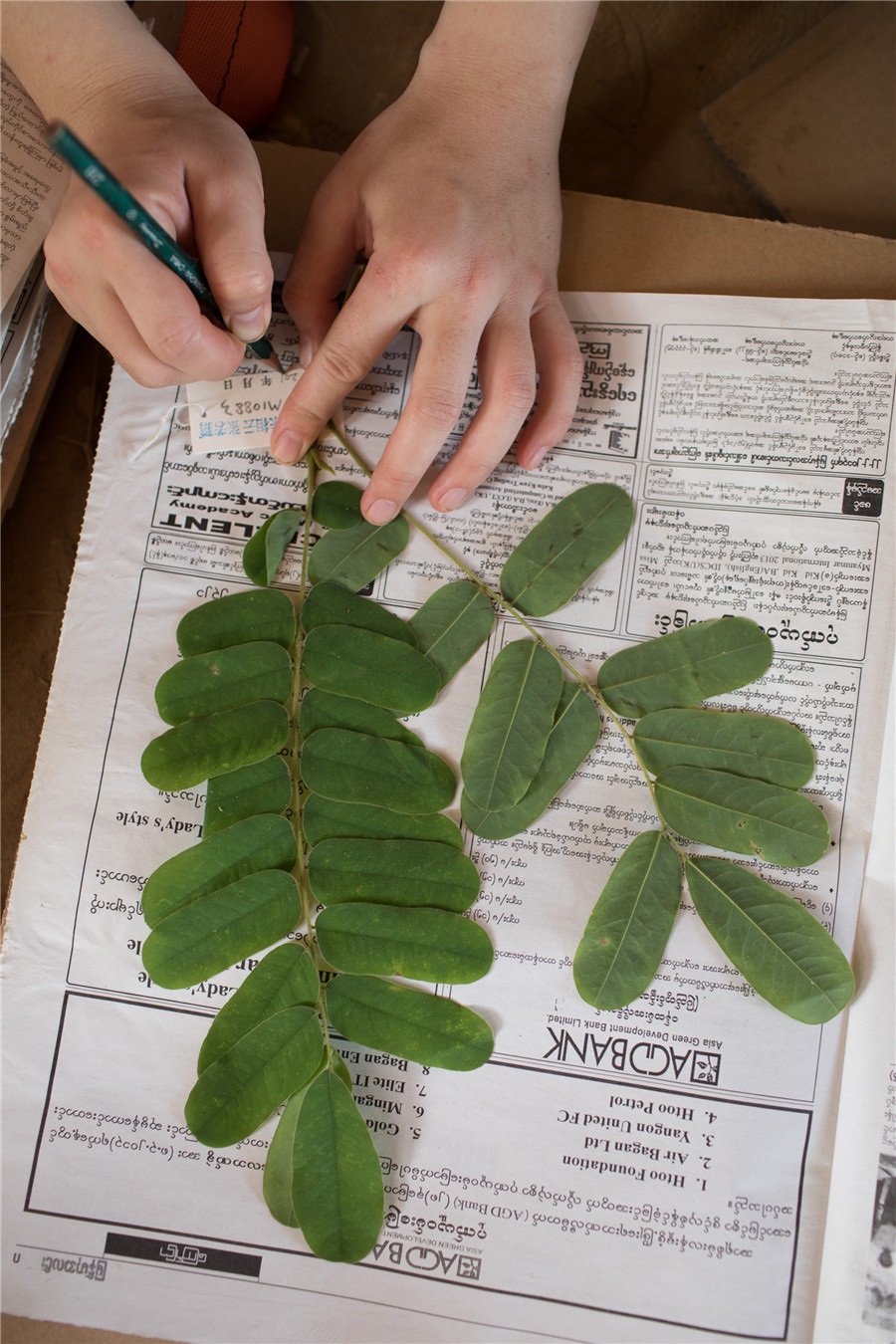

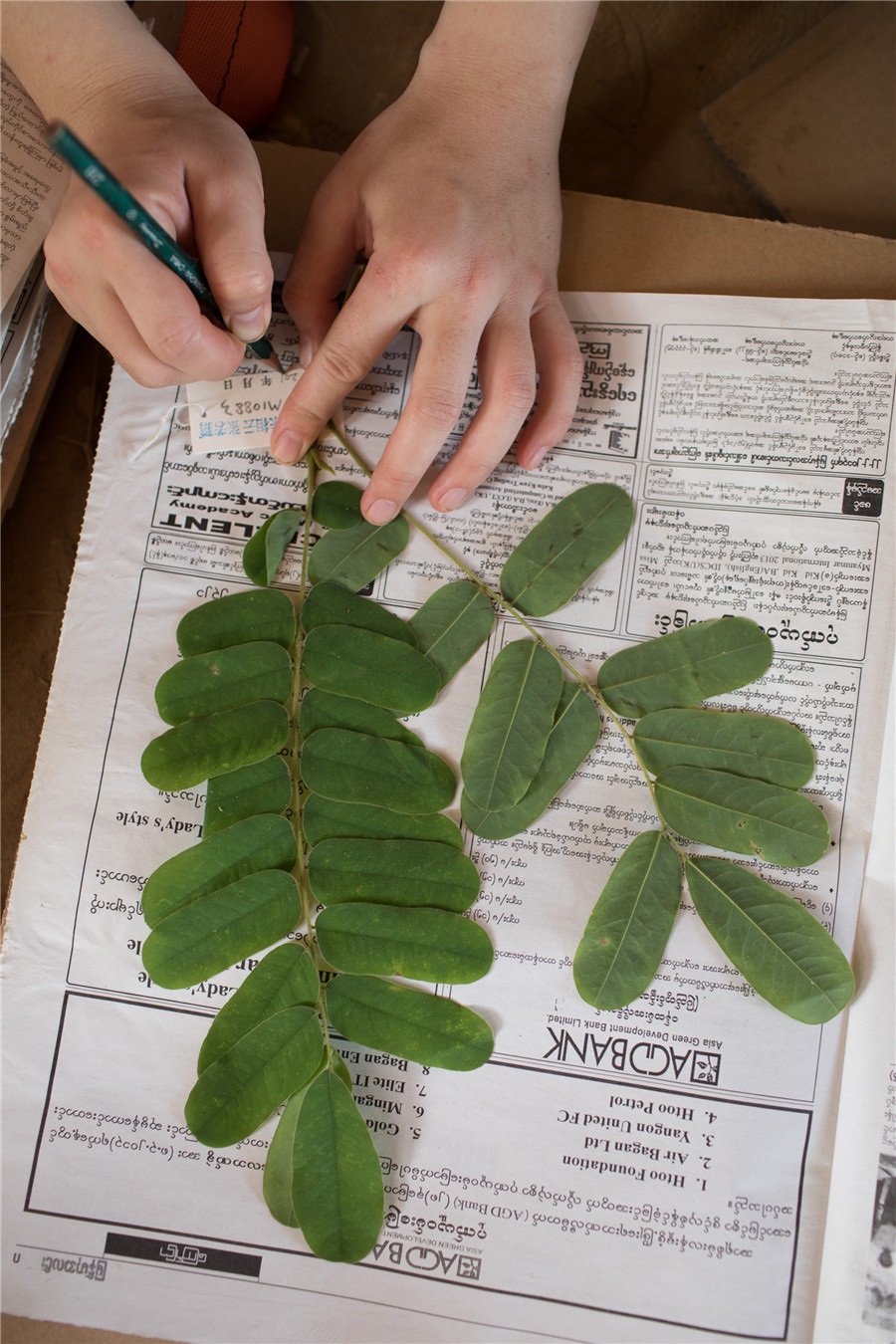

Researchers record plant samples. [Photo/Xinhua]

New species

Officially established in 2015, Quan's institute has conducted research in Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia, discovering at least 373 new species. It said it has also published more than 200 papers in major international journals, including Science and Systematic Biology.

The China-Myanmar joint field expedition is just one of 56 international projects with which Quan's center has been involved.

Though he believes that the team's efforts will help promote the protection of biodiversity in Myanmar, which still lacks adequate capabilities in terms of funding and carrying out independent scientific research on the subject, he said he often feels a sense of inadequacy.

"When looking at the map, I feel very disappointed," he said, adding that the teams have only set foot on a very limited area of the primitive forests that span almost 100,000 square kilometers of northern Myanmar, offering habitats to rich biodiversity resources as yet mostly unknown by the outside world.

The geographical conditions in the region, featuring high mountains and deep canyons, make it hard to undertake large-scale expeditions, he said.

Members of the expedition set up infrared cameras to monitor the activities of wild animals. [Photo/Xinhua]

New generation

However, Quan may gradually feel relieved thanks to a project that aims to cultivate homegrown ecologists in Myanmar and a number of Asian countries.

According to the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, from 2016 to last year, 86 students from Southeast Asian countries enrolled at CAS institutes via the center to study for master's degrees or doctorates in biodiversity. Among them, 49 were from Myanmar.

"We enroll about 10 students from Myanmar every year. This is a good beginning to promote sustainable development in the country's biodiversity protection by helping Myanmar build up its own scientific research teams," Quan said.

Myo Min Thein, an official from Myanmar who is studying for a master's in ecology at the botanical garden, said capacity building for ecologists is very important for his country, which is attaching growing importance to the protection of biodiversity.

"We are making more efforts. You know, we are a developing country and we need technology to help conservation," said the employee of the country's Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

The 28-year-old conducted a 45-day field study for his thesis titled "Plant-animal Interaction along the Elevation of Mount Victoria".

The botanical garden has encouraged him to return to Myanmar to carry out a field study for his thesis so the results can help address problems in the country, he said.

He is looking forward to making full use of what he has learned in China to help manage Myanmar's biodiversity resources after he graduates next year.

In 2009, the botanical garden launched an annual course to help improve biodiversity protection capability in tropical countries. Participants spend half of the 43-day course attending lectures given by senior scientists from home and abroad, and use the time remaining to conduct studies under the guidance of the senior experts, according to Chen Jin, director of the garden.

He said the course attracts students from at least 10 countries every year, and so far, 282 people from 24 countries, including many ecologists, have participated.

Chen said efforts have been made to build the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute into a research center that can facilitate academic exchanges about biodiversity protection in Southeast Asia among scientists from various countries.

"Though we have done a great deal of work, our efforts are far from sufficient to address the difficulties and challenges (of biodiversity protection) the region faces," he said, adding that climate change and regional development will further damage the rich biodiversity resources.

However, Song, the associate researcher, believes they have sown the seeds of hope as more students graduate from biodiversity protection courses in China. When they return to their home countries, the students will help to cultivate the biodiversity protection talent their countries need.

"More people will engage (in biodiversity protection). We don't know what results our efforts will yield, but at least we are working on the issue. There should be at least some differences, rather than if no efforts had been made," he said.

URL: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201910/14/WS5da3d51ea310cf3e35570493_1.html